Managing HF in CKD: Navigating complexity in dual pathology

18 Sep 2025

Share

Heart failure (HF) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are two major clinical syndromes that often coexist, amplifying each other’s progression in what is commonly described as a “vicious cycle.” At the 39th Malaysian Society of Nephrology (MSN) Annual Congress 2025, Dr. Norleen Zulkarnain Sim, consultant nephrologist at Hospital Tengku Ampuan Rahimah (HTAR) Klang, highlighted the clinical challenges and practical strategies in managing patients living with both conditions.

HF is a clinical syndrome marked by dyspnea, peripheral edema, and fatigue, with supportive signs such as lung crepitations, raised jugular venous pressure, and evidence of cardiac structural or functional abnormality. It is further classified by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) into reduced (HFrEF: <40%), mildly reduced (HFmrEF: 41-49%), and preserved (HFpEF: ≥50%). CKD, on the other hand, is defined by persistently reduced eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73m2 or presence of markers of kidney damage for more than three months. The two conditions frequently overlap, and as Dr. Norleen emphasized, “HF can precipitate kidney dysfunction, and CKD in turn worsens cardiac outcomes.”

The burden is substantial. CKD comorbidity carries the greatest population-attributable risk for hospitalization and all-cause mortality in HF. Meta-analysis data demonstrate that up to 55% of patients with either HFrEF or HFpEF have stage 3 CKD or worse, with mortality risk rising stepwise as kidney function declines. This bi-directional relationship, combined with overlapping risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, makes management particularly complex.

Diagnosis represents another challenge as symptoms like fatigue, dyspnea, and edema may originate from either organ system, complicating clinical judgment. Hence, imaging plays a crucial role, with echocardiography remaining central for evaluating ventricular function, wall thickness, valvular abnormalities, and filling pressures. Biomarkers, while helpful, must be interpreted with caution in CKD. NT-proBNP (N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide) remains a useful tool, while troponin T is prone to false positives in patients with impaired kidney function, limiting its specificity in diagnosing acute coronary syndromes. Novel biomarkers such as soluble ST2 and galectin-3 show promise for assessing cardiac fibrosis, but accessibility remains limited. Renal markers such as NGAL (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin) and cystatin C are also under investigation, though not widely adopted in everyday practice.

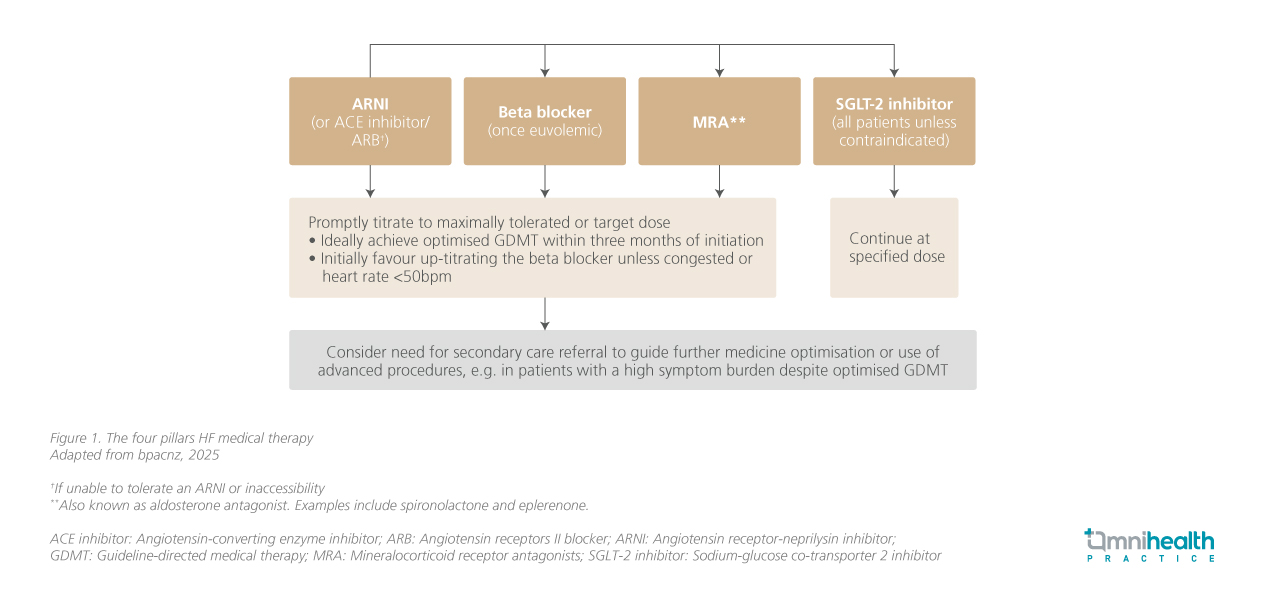

Once a diagnosis is established, management requires striking the right balance between efficacy and safety. Guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), or the “four pillars” of heart failure treatment, is the foundation of care but must be tailored and closely monitored in CKD. Fluid control is fundamental, with loop diuretics such as furosemide used to relieve congestion. In CKD, higher doses are often needed, and the intravenous route is preferred in acute decompensation. The key is to achieve euvolemia without tipping into dehydration, as persistent congestion with rising creatinine is a poor prognostic sign. As Dr. Norleen emphasized, initiation of the four pillars should be prioritized and tailored to patient tolerance, with close monitoring for renal function decline and hyperkalemia.

Anemia and iron deficiency further complicate the picture. Iron deficiency in particular has been shown to worsen outcomes more strongly than anemia alone. Intravenous iron therapy, such as ferric carboxymaltose, is therefore recommended in symptomatic patients with NYHA class II-IV, reduced EF, and biochemical evidence of iron deficiency (ferritin <100 µg/L or transferrin saturation <20%), regardless of anemia status. Timely and appropriate treatment improves functional capacity, quality of life, and reduces hospitalizations.

Beyond pharmacotherapy, referral for device-based therapies may be considered. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are guideline-recommended for patients at high risk of sudden cardiac death, but their benefits appear attenuated in CKD due to competing non-arrhythmic causes of death and reduced device efficacy. Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), in contrast, has shown improvements in renal function and reduced HF hospitalizations in selected CKD patients, highlighting the importance of individualized referral to cardiology.

Guideline recommendations provide a valuable framework, but their application in CKD is far from straightforward. The 2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines emphasize early initiation of disease-modifying therapies, while Malaysia’s 2023 5th edition of the Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) on HF reflects similar priorities but with adaptations suited to local healthcare settings. Both stress the need for multidisciplinary collaboration, which is especially critical in patients with these dual diagnoses.

In conclusion, managing HF in CKD remains a clinical challenge, particularly in advanced disease where evidence is scarce. Prevention of progression in both conditions is essential, and patients at risk should be monitored closely to enable timely intervention. A multidisciplinary approach, combined with careful use of evidence-based therapies, remains central to delivering holistic care for this complex patient group. The four therapeutic pillars of HF management in CKD, which form the foundation of such therapy, are summarized in figure 1.

In a discussion with Omnihealth Practice, Dr. Norleen Zulkarnain Sim spoke about the real-world challenges of managing HF in CKD and why early, tailored interventions make all the difference.

Q1: In your practice, what is the biggest challenge when managing patients with HF in CKD?

Dr. Norleen: As nephrologists, we often see patients who are already at an advanced stage of CKD upon referral. The difficulty is that once patients reach CKD stage 4 or 5, options become very restricted, and we are often left managing complications rather than modifying disease. This is why prevention and early intervention are important. If we can start and optimize therapies like renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors earlier, we have a much better chance of slowing renal progression and improving long-term outcomes. On top of that, we often need to balance multiple comorbidities, polypharmacy, and limited drug availability, which makes tailoring therapy to each patient essential.

Q2: How does hypoalbuminemia in CKD affect the management of heart failure?

Dr. Norleen: Low serum albumin is very common in CKD, and it carries both nutritional and prognostic implications. In the context of heart failure, hypoalbuminemia can worsen fluid overload because of reduced oncotic pressure, making patients more prone to edema and congestion. It also influences how well diuretics work, since these medications are protein-bound and less effective when albumin is low. In practice, this often means patients require higher doses to achieve the same effect, which adds to the complexity of care.

Q3: For patients with recurrent HF episodes, when should dialysis be considered?

Dr. Norleen: Recurrent hospitalizations for HF in the setting of advanced CKD are a red flag. In some cases, initiating dialysis can help with volume control and symptom relief, particularly if conventional diuretic strategies are no longer effective. It should not be seen only as a “last resort,” but rather as part of a broader strategy to stabilize patients who are otherwise struggling with repeated decompensation. The key is to individualize the timing and to involve both nephrology and cardiology teams early in the discussion.

References

- Zulkarnain Sim N. Managing heart failure in CKD. Presented at the 11th Asia Pacific Chapter Meeting of the International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis (APCM-ISPD) in conjunction with the 39th Annual Congress of the Malaysian Society of Nephrology (MSN) 2025; Sep 3-7, 2025.

- Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand (bpacnz). bpacnz Clinical Audit: Optimising Treatment in Patients with Heart Failure. 2025. Available from: https://bpac.org.nz/Audits/docs/bpacnz_audit_heart_failure_treatment.pdf